A new world of learning

As our TIESEA project moves further into its exciting interventions phase it is timely to consider what happens next in learning?

We are at the start of the most exciting decade for learning ever, for a number of reasons. This new decade offers dramatic learning opportunities to communities and nations regardless of their staring points; a genuine levelling of opportunity. This short blog post begins the explanation of what those opportunities are, some of the reasons for them, and why it matters most for our TIESEA nations.

Firstly, the global impact of the pandemic on learning was profound. Around the locked-down world, children learned in new ways and in new places. The least successful of these were the attempts to carry on as before but with an analog of the classroom via Zoom or Teams. Same timetable, different locations.

“Good morning class. It’s 11:30 and time for our chemistry lesson. Cameras on, microphones off please”.

These analogs failed for many reasons, but principally there was an equity issue – many families simply could not all be live online at the same time; secondly these Zoomed lessons were hardly engaging and few children were stretched cognitively by sitting in front of screen watching their teacher.

However, the more successful lock-down lessons were asynchronous, had touch-points of plenary activity, and expected collaborative endeavour away from screens too. Better still, children found themselves in mixed age communities of learners, often including a parent or grandparent too; they exercised voice and vote over the direction of their learning. A research survey we posted (heppell.net/golden) revealed that in all of our research population of many thousands, not one child recorded pride in the BREADTH of curriculum covered, whilst almost all recorded with pride the DEPTH they had achieved in their chosen topic or topics. Deep learning and “learning elsewhere” triumphed.

Secondly, Learning has become über-fashionable in all our lives. Peak time TV shows around the world reveal celebrities learning to cook, or to sew, or dance… Some of the biggest audiences for YouTube videos are following the huge number of “How to” guides. TikTok has curated many truly exceptional learning moments each with their own dedicated audience (for example see tiktok.com/@tinyphysicslab). Learning has never been more cool.

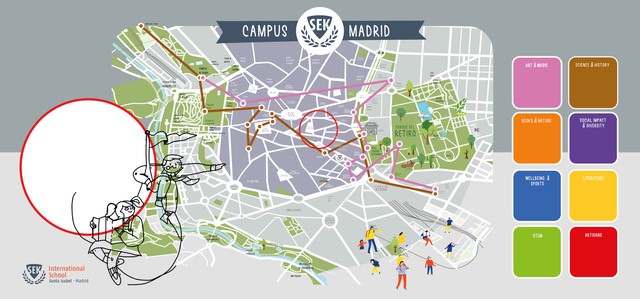

And “learning elsewhere” quickly validated “learning outside”. This side of the pandemic, the move to explore outdoor learning is substantial and widespread. Children don’t want to be back in their boxes. In Madrid the tiny St Isabel International SEK School, with no outside play space, has created learning journeys throughout central Madrid (https://santaisabel.sek.es/en/the-school/learning-spaces/). Teachers have built these wonderful journeys around a curriculum focus and the destination of each walk is something of note within that urban community: pasta making, a jazz workshop, an embassy, a botanical garden – a great variety but importantly embedding the skills, resources and culture of the community in the formal learning of the school. On England’s East Coast Beachschool.org have the youngest children immersed in the data, flora and fauna of their beach’s marine science. The children are directly in tune with the seasons, the cycles and the exceptions on their coast. More importantly, their knowledge and interest have built a bridge into the old traditional community of oyster fishing and water conservation. Local experts suddenly have an engaged generation to pass their deep knowledge on to, and to learn from. It turns out that when you learn elsewhere, their is much of value, freely contributed, in our communities and families. There is no physical building at all. The beach is the centre of their learning, whatever the weather. That model is now being replicated on the banks of the Amazon in Colombia for the indigenous children of the rainforest.

In short, post pandemic, some learning has escaped. It’s escaped from the classrooms and timetables, it has escaped from the age phase structures and the “individual learner” focus of schools and it has escaped from much of the need for capital expenditure. With hybrid online learning, much stronger community collaborations and a greater outdoor focus it is clear that we can often do better learning for less capital expenditure and can see the results very quickly indeed. The implications for our TIESEA community are clear. And by pooling the important details to build economies of scale – for example in the curation of resources – we can gallop past richer economies struggling to maintain their expensive legacy systems.

It’s going to be a very exciting decade ahead.

TIESEA project member Professor Stephen Heppell.

Brightlingsea’s Beachschool children with their buckets and hand held digital microscopes

Brightlingsea’s Beachschool is all about the science – here exploring capillary tracking

Mapping some of the learning journeys around the centre of Madrid – now very much a part of the St Isabel wide campus.

St Isabel children embarking on one of their regular learning journeys. Note the community figures watching over their safety!

How NOT to use EdTech in your classroom

As teachers, we all know that we are likely to find a range of abilities in any class group. In June this year (2022) the World Bank revealed that the level of ‘learning poverty’ in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) has been exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic. An estimated 7 in 10 of all children in LMICs cannot read a simple text with comprehension by age 10. [1] These children are fated to fall further and further behind as they progress to higher grade levels where the ability to read becomes increasingly important. The issue of learning poverty is often compounded by textbooks exceeding the reading level of most students of the class. Indian education economist Karthik Muralidharan notes that in many struggling education systems, “textbooks are usually written by elites and only benefit the best students” (Mirchandani 2015). [2] Faced with such challenges, teachers often resort to teaching to the middle of the class, or even to the top of the class, guaranteeing that some of their students will be left behind.

How can education technology (EdTech) enable teachers to address such constraints to learning?

It is increasingly thought that the answer lies in differentiated learning. The UNESCO International Bureau of Education defines differentiated learning as ‘An approach to teaching that involves offering several different learning experiences and proactively addressing students’ varied needs to maximize learning opportunities for each student in the classroom.’[3]

In high-tech environments where students have access to individual devices, this can involve using tools such as Nearpod or Blendspace to curate lesson workflows for different students or student groups. Nearpod provides real-time insights into student understanding through interactive lessons andvideos, gamification, and activities. This allows teachers to create customized activities for self-paced individual work or group work at the ‘right level’. Blendspace allows teachers to draw together digital materials from a range of sources to create individualized learning spaces. To ensure that material is presented at an appropriate level, teachers can make use of resources such as Newsela which provides Science & Math, Social Studies, and Socio-Emotional Learning content at 5 reading levels. In specific subject areas, there is an increasing range of tools that use artificial intelligence (AI) to automatically select content based on student performance so that the student is always presented content at a level which is slightly challenging for them without being overwhelming. Examples include i-Ready personalised learning in Reading and Mathematics for grades K-8 and the Khan Academy tools for learning Science and Math concepts.

The key to differentiated learning is using formative assessment to adjust the learning experience for the student. While AI enables an increasing range of personalised learning software to do this automatically, teachers can also draw on digital formative assessment tools to give them quick assessments of student’s understanding enabling them – to manually adjust their teaching. Options include Socrative, Poll Anywhere, Mentimeter, or Kahoot. All of these tools provide quick assessments of student understanding in a fun, anonymous and hence stress-less manner. EdPuzzle allows teachers to integrate quizzes into videos. ASSISTments allows Math teachers to assign problem sets; students doing the exercise get automatic feedback while the teacher receives reports on their performance.

There is increasing evidence for the value of formative assessment, or “assessment for learning” (Wiliam 2013). This assessment is not primarily about collecting data on students’ performance but as , Benjamin Bloom observed half a century ago, “We see much more effective use of formative evaluation if it is separated from the grading process and used primarily as an aid to teaching” (Bloom 1969, p. 48). Formative assessment takes place during learning, not after. [4]

Why then do we so often see teachers neglecting formative assessment options, ignoring the needs of individual learners in their class, and using EdTech to support teacher-centered pedagogies? Content-heavy PowerPoint presentations or even textbook exercises are projected onto a screen or SmartTV forcing all students to move through the lesson at the same pace (or to switch off). Digitized games which could be highly motivational if used on individual devices are likewise projected to the whole class discouraging all but a small percentage from participating. Is this helping the teacher? Most definitely. It reduces preparation time, particularly if the digital materials are provided by a textbook publisher as is common in some countries, and if materials can be reused the following year. Focusing student attention to the front of the room also helps maintain teacher control of the class. Is it helping the students? Generally, not. These scenarios only represent the digitization of traditional teacher-centered pedagogies and cater to a small portion of the class while less able students fall further and further behind.

The Technology-Enabled Innovation in South-East Asia (TIESEA) project recognises the importance of learner-centered pedagogies and strives to use EdTech to promote and support such approaches. In Viet Nam, the project will pilot the use of the Elsa Speak app which uses AI to help students of English improve their pronunciation skills. Students will be provided with smartphones which they can use to practice at home. This recognises research that found higher achievement levels in interventions that effectively extended the school day. [5] Teachers will receive training in how to facilitate communicative English as mandated by the government of Viet Nam in their latest curriculum revision. In Cambodia and Indonesia, STEM students who live in small communities close to their school will be able to work on real world projects together using Internet resources accessed through a mesh network (Cambodia) or from an offline content server (Indonesia and Cambodia). Once again, teachers will be supported with training in learner-centered teaching approaches. In Indonesia, this will be done with the assistance of Guru Penggerak – teachers in model schools trained to implement the Ministry of Education and Culture’s progressive Kurikulum Merdeka and, in Cambodia, by the Kampuchea Action to Promote Education (KAPE) NGO.

The implementation plan for the TIESEA pilot can be found here.

[1] https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2022/06/23/70-of-10-year-olds-now-in-learning-poverty-unable-to-read-and-understand-a-simple-text#:~:text=An%20estimated%207%20in%2010,This%20is%20unacceptable.

[2] Smart, A & Jagannathan, S (2018): Textbook Policies in Asia – Development, Publishing, Printing, Distribution and Future Implications, Asian Development Bank

[3] The UNESCO International Bureau of Education defines Differentiated Learning as An approach to teaching that involves offering several different learning experiences and proactively addressing students’ varied needs to maximize learning opportunities for each student in the classroom.

[4] Smart, A & Jagannathan, S (2018): Textbook Policies in Asia – Development, Publishing, Printing, Distribution and Future Implications, Asian Development Bank

[5] Ma, Y., Fairlie, R.W., Loyalka, P., & Rozelle, S. (2020), Isolating the “TECH” from EdTech: Experimental evidence on computer assisted learning in China, National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper 26953, Cambridge, MA

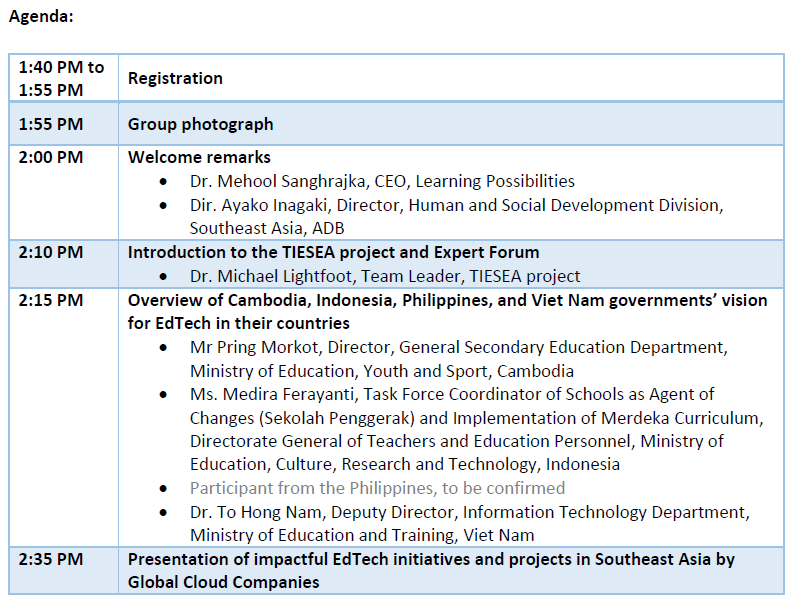

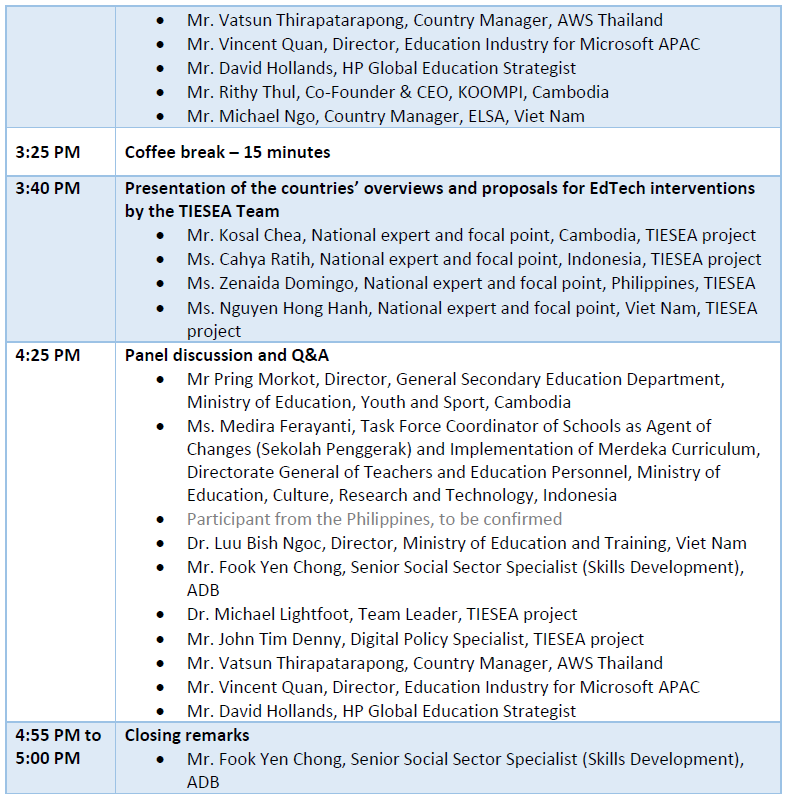

TIESEA webinar at BETT Asia

After a gap of two years, we are delighted to be presenting the TIESEA project at BETT Asia in Bangkok, Thailand on 11th October 2022.

Technology has played a key part in maintaining the continuity of education in region: during the past two years of disruption’ some solutions and tech intervention has been more successful than others. The TIESEA project team have conducted diagnostic assessments and analyses in each of the four project countries of: Cambodia, Indonesia, the Philippines, and Viet Nam. On the basis of the reports from these analyses, the project is currently implementing pilot studies in each country focusing on local needs and capacity building.

The webinar will outline the local situation, country by country, and seek to demonstrate how the project interventions can overcome obstacles in order to maximise the contribution that EdTech can make to both students’ achievement and the quality of learning in the region. There will also be leading industry experts and senior government leaders to share their experiences.

If you would like to attend, please contact us at info@lpplus.com

For more information on the TIESEA project, view the brochure here.

- Published in All Reports, Articles

“Tech-Inclusive Education: A World-Class System for Every Child” A discussion paper from the Institute for Global Change

“Tech-Inclusive Education: A World-Class System for Every Child”

A discussion paper from the Institute for Global Change[1]

Dr Philip Uys, KE3

29 August 2022

Summary Blog from Dr Philip Uys, EdTech Specialist, TIESEA project

During Covid-19 all manner of technology was deployed to keep children learning. There is a need to create places for more than 270 million more school pupils a year by 2030 – the largest expansion of school education in history. The scale of the challenge demands an immediate step change in how we think about the role of technology in education – Technology holds the promise of overcoming these fundamental challenges – a promise that so far remains unfulfilled.

The Report’s state the goals of an effective edtech approach as:

|

To give every child access to a world-class education system, we must move on from the debate between “tech-driven” or “tech-assisted” approaches and become “tech-inclusive.

A world-class education system for every child should ensure that all school-age children achieve at least minimum proficiency levels in core subjects, and address quality gaps faced by disadvantaged, disabled or otherwise discriminated-against students. |

What are indicated that do not work:

- the OECD found no direct link between class size and student performance

- technology is seen as a way to replace educators or dramatically reduce their role, and the future of education is primarily or entirely digital. At best, this allows for reductions in the cost of large-scale delivery with a significant negative impact on the quality of learning. During Covid 19 we saw the failure of technology when running up against the constraints of connectivity and device access, lack of physical space for learning and the need to develop digital skills

- The alternative, which has gained much ground recently, might be called “tech-assisted”. The argument here is that technology is at its best when it enhances what teachers already do, supporting tried-and-tested pedagogical methods or saving time. Insights from interactive platforms can also inform a more personalised approach to teaching. Digital platforms can help scale “teaching at the right level” programmes, which rely on an initial assessment as well as on ongoing tests to assign students content and activities that are most relevant to their level of knowledge. However, tech-assisted education must, by definition, fit within the constraints of existing approaches and is therefore limited in its ability to resolve the crisis trilemma. During Covid 19 we also saw that moving traditional ways of teaching online without adapting them to this new digital context resulted in subpar learning experiences

- improving access to hardware alone does not improve test scores.

Edtechs and initiatives highlighted in the Report are: Kahoot!, Nearpod, Mindspark, Oak National Academy, Sparx Maths, Eneza Education, Rising Academy Network, onebillion, Kolibri, Generation Global, UNICEF’s Learning Passport.

This report proposes a new way of thinking about reform: the “minimum viable education system” framework in line with the UN’s Sustainable Development Goal 4 to realise inclusive and equitable quality education for all. Governments should aim to reach the baseline level across each dimension first, because the fundamental reason for the education crisis is that these three policy goals are in tension with each other, and the current design of school systems is not equal to resolving these tensions:

- Designing and delivering high-quality education that meets the learning needs of children and supports future economic growth.

- Meeting the logistical and systems-design challenges of providing equal access to education for all children.

- Funding the education system at a public cost that is sustainable in the long term.

Their framework lays out what a minimum acceptable level of quality looks like across each dimension in any given context.

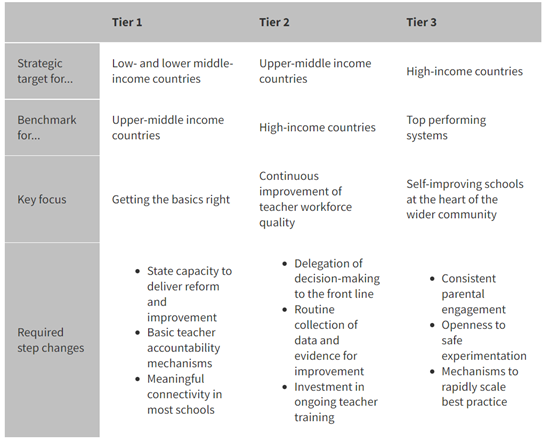

Systems’ starting points will differ. To account for these differences, the “minimum viable education system” framework defines three tiers, each building on the next. It can serve as both a benchmarking tool and a guide to strategic development. It is summarised (with more detail provided in the report for the system; infrastructure; teachers; learners; parents and carers) as:

- Tier 1is characterised by a focus on getting the basics right. Previous researchhas found that poorly performing systems that improve most rapidly are characterised by higher levels of centralisation, wider use of direct instruction and scaffolding for low-skilled teachers, and a focus on fundamentals of numeracy and literacy. To make the most of technology, systems at this tier must also provide meaningful connectivity and a basic level of access to devices, which may require significant early investment. Achieving performance at this tier would represent a significant improvement for most low- and lower-middle-income countries, where only a few schools might currently meet it, while upper-middle-income countries would often perform at or near this level.

- Tier 2 is characterised by growing levels of school autonomy and a focus on continuous improvement of the quality of the teacher workforce. Other aspects include stronger accountability, including to parents, and increasing attention to non-academic elements of schooling such as careers education or extracurricular activities. Many high-income countries will operate at this tier already, although some may need to ensure performance is equal across the entire system.

- Tier 3represents a self-improving system where schools go above and beyond their role as teaching institutions, providing support in the community and supporting the development of pupils as citizens as well as learners. Within such a system there is now sufficient capacity for far-reaching reforms and effective experimentation with technology as well as new pedagogies such as dialogue educationat the national scale, without neglecting the foundations of good learning. Very few, if any, of the leading school systems will be operating at this level today, although many of the best schools in high-income countries do this to some extent.

Advantages of the MVES approach: The value of a minimum viable education system is twofold. First, its implementation at the right tier improves resilience and levels up standards across the system, minimising inequities in access to quality education. Second, it creates the conditions for radical, tech-inclusive reforms within the system by ensuring that all schools, rather than just a few, have the infrastructure, skills and support necessary to use technology effectively.

Use of the MVES approach: Governments in low-income countries can use the MVES approach to assess whether their strategic development plans would assist with reaching Tier 1 and whether resources are allocated appropriately between the different dimensions. International donors can also adopt the framework to evaluate whether the focus of sponsored projects (for example, school-construction efforts or careers education) would support grantee countries in reaching the appropriate minimum viable tier. For governments in high-income settings, the framework can address inequality by helping to identify both gaps in the system that require “levelling up” and areas of overinvestment. It can also inform plans for future reform.

In line with the Framework policymakers – within an iterative mindset:

- In the short term (one to two years), international organisations such as UNESCO should address existing gaps in access to education by funding and building a remote World Education Service (WES), free at the point of delivery and accessible to all through the internet as well as low-tech channels like feature phones.

- In the medium term (three to seven years), national governments should build capacity for the effective use of technology through strategic investment in “minimum viable education systems”, with a holistic approach to the elements of school systems that affect the rate of adoption and the impact of education technology.

- In the long term (five to ten years), national governments should pilot and scale up radical reforms that maximise the potential of technology to deliver quality education at scale and at sustainable cost, such as:.

- Governments should look at adapting existing digital-ID infrastructure (or projects in development) to the “learner record” use case and seek consultation on issuing digital IDs at an earlier age than is usual today.

- Edtech providers should commit to making their systems interoperable with national digital learner IDs, and collaborate with governments, educators and learners on the development of a shared schema to allow cross-border integrations.

Reorganise classrooms into cohorts and transform teaching career paths, providing students with access to varied learning activities and in-person support, and allowing trainee teachers to draw on the subject knowledge of more experienced colleagues as they work in teams to deliver a mix of small-group tuition and high-quality digital learning for larger groups.

Next Steps

- Governments should run pilots with larger cohorts accompanied by teaching teams in select schools and at different age groups (primary, lower secondary, upper secondary) to assess impact and inform initial teacher-training reforms. Inspection regimes should be adapted to allow for such experimentation, and ensure its impact on learner experiences and outcomes is consistently captured.

- For this scenario to be cost effective, it must be delivered at large scale, requiring significant investment in school infrastructure (electricity, connectivity and device availability). Governments should closely engage with existing initiatives such as Giga and accelerate their journeys towards universal internet access.

Break the link between geography and educational opportunities and expand choice for pupils and parents by putting in place infrastructure and regulation for “in-person remote” schooling. Remote learning hubs can complement remote school places by providing supervision from trained and vetted staff, peer socialisation and a suitable working environment.

Next Steps

- Governments should consider the implications of increasing the availability of remote, school-delivered learning on existing funding formulas, and design more flexible and transferable models.

- School-inspection bodies should be adapted in response to the wider availability of remote online schooling, creating mechanisms for “digital inspection” and putting clear quality-assurance frameworks and accountability measures in place (including cybersecurity requirements).

[1] Institute for Global Change (2021 Dec 07). https://institute.global/policy/tech-inclusive-education-world-class-system-every-child

- Published in Blog

- 1

- 2