Intensive Pedagogy Training

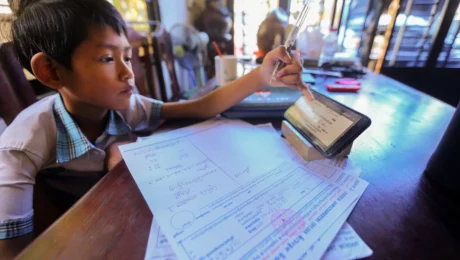

Our schools in Cambodia have just completed two training workshops with KAPE (Kampuchea Action to Promote Education). Using table computers, projectors and content stored on Koompi offline servers in their science classrooms, teachers are creating activity-based STEM learning environments for their students. Much of the content has been assembled by the Centre for Digital and Distance Education and is in Khmer language.

- Published in Cambodia All Reports, Cambodia Articles, Cambodia News

The TIESEA pilot project in Cambodia is being implemented in three schools

- Koh Khsach Tunlea Lower Secondary School. At this school students in grade 8 will learn from Khmer language STEM eLearning content saved on an offline content server and accessed through a tablet computer. Each student will have the privilege of taking their tab home after school to study further.

- Koh Khel Lower Secondary school. Grade 8 students will learn in the same way but will not be able to take their tabs home with them.

- Anlong Tasek Secondary School. Students will receive no project support but teachers will be invited to participate in teacher training.

|

|

Kosal Chea |

|

Independent Expert – Cambodia |

- Published in Cambodia All Reports, Cambodia Pilot Interventions

Strategy 2030: Achieving a Prosperous, Inclusive, Resilient, and Sustainable Asia and the Pacific

Asia and the Pacific has made great strides in poverty reduction and economic growth in the past 50 years. ADB has been a key partner in the significant transformation of the region and is committed to continue serving the region in the next phase of its development.

Under Strategy 2030, ADB will expand its vision to achieve a prosperous, inclusive, resilient, and sustainable Asia and the Pacific, while sustaining its efforts to eradicate extreme poverty.

- Asia and the Pacific has made great strides in poverty reduction and economic growth in the past 50 years, but there are unfinished development agendas. #Strategy2030

- Under the new #Strategy2030, ADB will sustain its efforts to eradicate extreme poverty while expanding its vision of a prosperous, inclusive, resilient, and sustainable Asia and the Pacific

- ADB will combine finance, knowledge, and partnerships to fulfill its expanded vision under the new #Strategy2030

View the brochure in other languages:

| Azeri | German | Myanmar | Thai | |

| Bahasa | Italian | Nepali | Urdu | |

| Chinese | Japanese | Pashto | Vietnamese | |

| Dari | Lao | Russian | ||

| French | Mongolian | Tetum |

ADB’s Strategy 2030: Responding to a Changing Asia and the Pacific

Contents

- Executive Summary

- Introduction

- Changing Landscape and Challenges

- ADB’s Vision and Value Addition

- Guiding Principles for ADB’s Operations

- Differentiated Approaches to Groups of Countries

- Operational Priorities

- Expanding Private Sector Operations

- Catalyzing and Mobilizing Financial Resources for Development

- Strengthening Knowledge Services

- Delivering through a Stronger, Better, and Faster ADB

- One ADB

- Appendix: Stocktaking of ADB Operations and Summary of Consultations

Additional Details

| Type | |

| Subjects |

|

| Pages |

|

| Dimensions |

|

| SKU |

|

| ISBN |

|

- Published in News, Related Content

How Teachers Teach: Comparing Classroom Pedagogical Practices in the Asia and Pacific Region

The brief draws together evidence on teaching practices in 18 economies in Asia and the Pacific and compares this with assessments of learning outcomes, including student perceptions of interactive teaching practices. The analysis reveals generally poor teaching across large parts of the region. It also highlights some whole-class approaches that appear to foster higher-order thinking skills, showing that there is not one universal approach to effective teaching.

As policy makers consider how to tackle the learning crisis, it is important to note that online learning and other uses of technology are unlikely to improve learning outcomes in the absence of good teaching. Overall, this paper adds to the evidence base showing the critical need to focus on improving teaching practice in order to get children learning.

Additional Details

| Authors | |

| Type | |

| Series | |

| Subjects |

|

| Countries/Economies |

|

| Pages |

|

| Dimensions |

|

| SKU |

|

| ISBN |

|

| ISSN |

|

- Published in News, Related Content

Regional: Technology-Enabled Innovation in Education in Southeast Asia

The proposed knowledge and support technical assistance (TA) will conduct a diagnostic of what works in education technology (EdTech) in Cambodia, Indonesia, the Philippines, and Viet Nam. It will identify at what level technology solutions can be used based on ‘EdTech Readiness’ of countries, and pilot EdTech interventions accordingly. The TA builds on an ongoing regional TA on innovation in education sector development, which also focuses on Cambodia, Indonesia, the Philippines, and Viet Nam. The ongoing regional TA assessed the impact of the fourth industrial revolution (4IR) on labor markets by examining two economically important sectors in each country. The proposed TA builds on one of the key lessons from the ongoing regional TA: the need to leverage technology to provide trainings and skills development.

Latest Project Documents

| Title | Date |

|---|---|

| Technology-Enabled Innovation in Education in Southeast Asia: Technical Assistance Report | Dec 2020 |

Read the full article here.

- Published in News, Related Content

Education is in Crisis: How Can Technology be Part of the Solution?

By Paul Vandenberg, Kirsty Newman, Milan Thomas

Digital technologies and EdTech could play a role in addressing the learning crisis underway in Asia and the Pacific.

A learning crisis affects many developing countries in Asia. Millions of children attend school but are not learning enough. They cannot read, write, or do mathematics at their grade level, and yet they pass to the next grade, learning even less because they have not grasped the previous material. The magnitude of the crisis is staggering: in low- and middle-income countries more than half of children are not learning to read by age 10.

At the same time, there is an emerging revolution in learning brought on by digital technologies. These are collectively referred to as educational technology or EdTech. The coincident emergence of a problem in education and a new approach to learning naturally makes us ask how one may be a solution for the other.

Edtech may be one part of the solution – but it should be a means not an end. Our guiding principle should be to first diagnose what is going wrong in a system and then identify which solutions are best suited to solve those problems.

Some causes of the learning crisis are well understood. The poor quality of teaching is a key factor. Teachers often lack subject knowledge and have not had adequate training. There are ways in which technology could address this – and so EdTech may be equally valuable in teaching teachers as it is in teaching students. By offering distance learning, EdTech can provide in-service training or combine online and in-person training (blended learning).

There is also evidence that teachers need better incentives. The idea is that that they can teach well but are not motivated to do so. It is not clear how EdTech can address this problem. Digitized school management systems could better track teacher performance (by tracking their students’ performance) and then linking to pay or other incentives. However, the main need is to design the incentive system; digital applications may only make that system more efficient.

Computer-assisted learning is the direct means by which EdTech can help students. It can be seen as a partial solution for two fundamental learning crisis problems: addressing students at different learning levels and completing the syllabus. A classroom contains students with a range of baseline learning levels and teachers are often incentivized to teach to the upper stratum, leaving many students behind. Furthermore, teachers are pressured to cover the syllabus by year’s end. They move on to new material even if students have not mastered previous lessons. This also leaves students behind.

The solution to both problems is, of course, more tailored teaching, but a teacher is hard-pressed to provide one-on-one tutoring to 30 or 40 kids. EdTech might help provide one-to-one instruction (e.g., one student to one tablet) so pupils can learn at their own level and pace. The evidence from rigorous assessments (largely in the United States) is that packages that use artificial intelligence to adjust to a student’s level can improve results, especially in math.

However, we need to be cautious. Most of the evidence comes from contexts in which the quality of teaching is already quite good and is much above the average in developing countries. Digital systems can also help increase the efficiency of formative assessment and make it more likely that such assessment will be conducted. Tracking of students’ learning, through data collection and analysis, can help to better monitor a student’s learning level and provide level-appropriate teaching and remediation.

Computer-assisted learning is the direct means by which EdTech can help students.

Edtech software, introduced in conjunction with other reforms, holds some promise. One notable success is Mindspark in India, which improves math and Hindi learning. It has been evaluated as an after-hours supplement and combined with human teaching assistance. More assessments of programs would be helpful.

There is also evidence that low-tech interventions for “teaching at the right level” can also have large impacts on learning. Careful analysis is needed to determine whether high-tech or low-tech solutions are best, given that low tech is less costly, and finance is a constraint in poor countries.

The COVID-19 pandemic has given a big push to EdTech. We can learn from these experiences but need to keep them in context. EdTech is being used to overcome the need to social distance. Teachers are teaching by video but not necessarily teaching better than when standing in front of a classroom. Zoom fatigue is a problem. More mass open online courses are being offered and are being taken up – but much of this is not for basic education and therefore does not address the learning crisis.

Supporting EdTech solutions comes with four caveats. First, new initiatives need to be well-designed to address specific weaknesses. Low-quality teacher training delivered partially online is no better than low-quality in-person training. The same applies to computer-assisted learning.

Second, computer-assisted learning is often used in schools or in after-hours programs at or near schools. Delivering as distance learning is trickier. It requires hardware and connectivity at home, which is not available to children in low-income households in developing countries and even developed ones.

Third, EdTech programs used outside normal classroom hours adds to the time children spend learning. This is good but it is not always clear whether the benefits are coming from EdTech, per se, or simply more time spent learning. Nonetheless, gamification and other techniques may make children want to spend more time learning.

Finally, let us keep in mind that good learning outcomes can be achieved without EdTech. Developed countries got results before the advent of EdTech. So too did good schools in developing countries.

To be effective, EdTech must address key causes of the crisis and be part of a larger package of reforms. Those reforms include teacher training, incentives, monitoring, teaching at the right level, remediation for underperforming students, and others.

Digital technologies have changed our lives in many ways, mostly for the good. EdTech could do the same by playing a role in addressing the learning crisis.

- Published in News, Related Content

- 1

- 2