“Tech-Inclusive Education: A World-Class System for Every Child”

A discussion paper from the Institute for Global Change[1]

Dr Philip Uys, KE3

29 August 2022

Summary Blog from Dr Philip Uys, EdTech Specialist, TIESEA project

During Covid-19 all manner of technology was deployed to keep children learning. There is a need to create places for more than 270 million more school pupils a year by 2030 – the largest expansion of school education in history. The scale of the challenge demands an immediate step change in how we think about the role of technology in education – Technology holds the promise of overcoming these fundamental challenges – a promise that so far remains unfulfilled.

The Report’s state the goals of an effective edtech approach as:

|

To give every child access to a world-class education system, we must move on from the debate between “tech-driven” or “tech-assisted” approaches and become “tech-inclusive.

A world-class education system for every child should ensure that all school-age children achieve at least minimum proficiency levels in core subjects, and address quality gaps faced by disadvantaged, disabled or otherwise discriminated-against students. |

What are indicated that do not work:

- the OECD found no direct link between class size and student performance

- technology is seen as a way to replace educators or dramatically reduce their role, and the future of education is primarily or entirely digital. At best, this allows for reductions in the cost of large-scale delivery with a significant negative impact on the quality of learning. During Covid 19 we saw the failure of technology when running up against the constraints of connectivity and device access, lack of physical space for learning and the need to develop digital skills

- The alternative, which has gained much ground recently, might be called “tech-assisted”. The argument here is that technology is at its best when it enhances what teachers already do, supporting tried-and-tested pedagogical methods or saving time. Insights from interactive platforms can also inform a more personalised approach to teaching. Digital platforms can help scale “teaching at the right level” programmes, which rely on an initial assessment as well as on ongoing tests to assign students content and activities that are most relevant to their level of knowledge. However, tech-assisted education must, by definition, fit within the constraints of existing approaches and is therefore limited in its ability to resolve the crisis trilemma. During Covid 19 we also saw that moving traditional ways of teaching online without adapting them to this new digital context resulted in subpar learning experiences

- improving access to hardware alone does not improve test scores.

Edtechs and initiatives highlighted in the Report are: Kahoot!, Nearpod, Mindspark, Oak National Academy, Sparx Maths, Eneza Education, Rising Academy Network, onebillion, Kolibri, Generation Global, UNICEF’s Learning Passport.

This report proposes a new way of thinking about reform: the “minimum viable education system” framework in line with the UN’s Sustainable Development Goal 4 to realise inclusive and equitable quality education for all. Governments should aim to reach the baseline level across each dimension first, because the fundamental reason for the education crisis is that these three policy goals are in tension with each other, and the current design of school systems is not equal to resolving these tensions:

- Designing and delivering high-quality education that meets the learning needs of children and supports future economic growth.

- Meeting the logistical and systems-design challenges of providing equal access to education for all children.

- Funding the education system at a public cost that is sustainable in the long term.

Their framework lays out what a minimum acceptable level of quality looks like across each dimension in any given context.

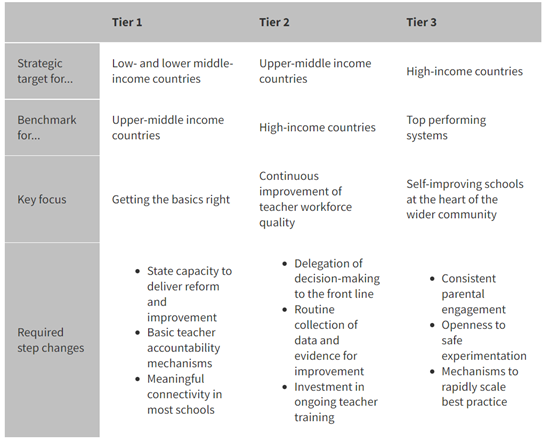

Systems’ starting points will differ. To account for these differences, the “minimum viable education system” framework defines three tiers, each building on the next. It can serve as both a benchmarking tool and a guide to strategic development. It is summarised (with more detail provided in the report for the system; infrastructure; teachers; learners; parents and carers) as:

- Tier 1is characterised by a focus on getting the basics right. Previous researchhas found that poorly performing systems that improve most rapidly are characterised by higher levels of centralisation, wider use of direct instruction and scaffolding for low-skilled teachers, and a focus on fundamentals of numeracy and literacy. To make the most of technology, systems at this tier must also provide meaningful connectivity and a basic level of access to devices, which may require significant early investment. Achieving performance at this tier would represent a significant improvement for most low- and lower-middle-income countries, where only a few schools might currently meet it, while upper-middle-income countries would often perform at or near this level.

- Tier 2 is characterised by growing levels of school autonomy and a focus on continuous improvement of the quality of the teacher workforce. Other aspects include stronger accountability, including to parents, and increasing attention to non-academic elements of schooling such as careers education or extracurricular activities. Many high-income countries will operate at this tier already, although some may need to ensure performance is equal across the entire system.

- Tier 3represents a self-improving system where schools go above and beyond their role as teaching institutions, providing support in the community and supporting the development of pupils as citizens as well as learners. Within such a system there is now sufficient capacity for far-reaching reforms and effective experimentation with technology as well as new pedagogies such as dialogue educationat the national scale, without neglecting the foundations of good learning. Very few, if any, of the leading school systems will be operating at this level today, although many of the best schools in high-income countries do this to some extent.

Advantages of the MVES approach: The value of a minimum viable education system is twofold. First, its implementation at the right tier improves resilience and levels up standards across the system, minimising inequities in access to quality education. Second, it creates the conditions for radical, tech-inclusive reforms within the system by ensuring that all schools, rather than just a few, have the infrastructure, skills and support necessary to use technology effectively.

Use of the MVES approach: Governments in low-income countries can use the MVES approach to assess whether their strategic development plans would assist with reaching Tier 1 and whether resources are allocated appropriately between the different dimensions. International donors can also adopt the framework to evaluate whether the focus of sponsored projects (for example, school-construction efforts or careers education) would support grantee countries in reaching the appropriate minimum viable tier. For governments in high-income settings, the framework can address inequality by helping to identify both gaps in the system that require “levelling up” and areas of overinvestment. It can also inform plans for future reform.

In line with the Framework policymakers – within an iterative mindset:

- In the short term (one to two years), international organisations such as UNESCO should address existing gaps in access to education by funding and building a remote World Education Service (WES), free at the point of delivery and accessible to all through the internet as well as low-tech channels like feature phones.

- In the medium term (three to seven years), national governments should build capacity for the effective use of technology through strategic investment in “minimum viable education systems”, with a holistic approach to the elements of school systems that affect the rate of adoption and the impact of education technology.

- In the long term (five to ten years), national governments should pilot and scale up radical reforms that maximise the potential of technology to deliver quality education at scale and at sustainable cost, such as:.

- Governments should look at adapting existing digital-ID infrastructure (or projects in development) to the “learner record” use case and seek consultation on issuing digital IDs at an earlier age than is usual today.

- Edtech providers should commit to making their systems interoperable with national digital learner IDs, and collaborate with governments, educators and learners on the development of a shared schema to allow cross-border integrations.

Reorganise classrooms into cohorts and transform teaching career paths, providing students with access to varied learning activities and in-person support, and allowing trainee teachers to draw on the subject knowledge of more experienced colleagues as they work in teams to deliver a mix of small-group tuition and high-quality digital learning for larger groups.

Next Steps

- Governments should run pilots with larger cohorts accompanied by teaching teams in select schools and at different age groups (primary, lower secondary, upper secondary) to assess impact and inform initial teacher-training reforms. Inspection regimes should be adapted to allow for such experimentation, and ensure its impact on learner experiences and outcomes is consistently captured.

- For this scenario to be cost effective, it must be delivered at large scale, requiring significant investment in school infrastructure (electricity, connectivity and device availability). Governments should closely engage with existing initiatives such as Giga and accelerate their journeys towards universal internet access.

Break the link between geography and educational opportunities and expand choice for pupils and parents by putting in place infrastructure and regulation for “in-person remote” schooling. Remote learning hubs can complement remote school places by providing supervision from trained and vetted staff, peer socialisation and a suitable working environment.

Next Steps

- Governments should consider the implications of increasing the availability of remote, school-delivered learning on existing funding formulas, and design more flexible and transferable models.

- School-inspection bodies should be adapted in response to the wider availability of remote online schooling, creating mechanisms for “digital inspection” and putting clear quality-assurance frameworks and accountability measures in place (including cybersecurity requirements).

[1] Institute for Global Change (2021 Dec 07). https://institute.global/policy/tech-inclusive-education-world-class-system-every-child